Evaluate a candidate by the Numbers

May I teach you a method to numerically evaluate candidates for public office? The method is derived from a field that combines engineering with economics. It is called “Value Engineering.” It is a way to examine and analyze all aspects of product, a component, or a service to make it the best it can be while, hopefully, saving money. The analysis can be detailed and often involves teams of people who bring skill and knowledge to the evaluation. But once an individual becomes familiar with the method, they can apply it themselves to virtually everything that is important to them. All that I have done is to show how the method can be applied to evaluating a political candidate. In this example, we will evaluate a presidential candidate.

A president, as with anyone who has a job to do, has tasks to complete. There will be constraints on how well s/he can perform those tasks. A “constraint” is anything that is an obstacle to performing the task. There are also resources to be drawn upon to accomplish the tasks. The president will bring to the job specific attributes or abilities, unique to him or her as a person. Of course, the individual’s supporters will inflate the value of some of these attributes. His or her detractors on the other hand are likely to minimize their importance or dismiss them altogether. Further, as a person, the president will be hobbled by various, specific deficiencies. That is, whether real or imaginary, the attributes will be counterbalanced by the deficiencies, and whoever is doing the evaluating will perceive them according to their own bias.

The ability to weigh the importance of the tasks, the quality of the attributes and the resources, and the negatives of both the constraints and the deficiencies, gives this method its strength. It allows the evaluator to factor in their bias while arriving at a conclusion, which can be compared or contrasted to that of another person going through the exercise.

When the evaluation is group-based, it is best to agree upon the evaluation criteria first. Then, each participant determines numerical scores individually. Finally, the scores are averaged to arrive at a consensus.

The method takes some time to learn and to use. What follows is a step-by-step example:

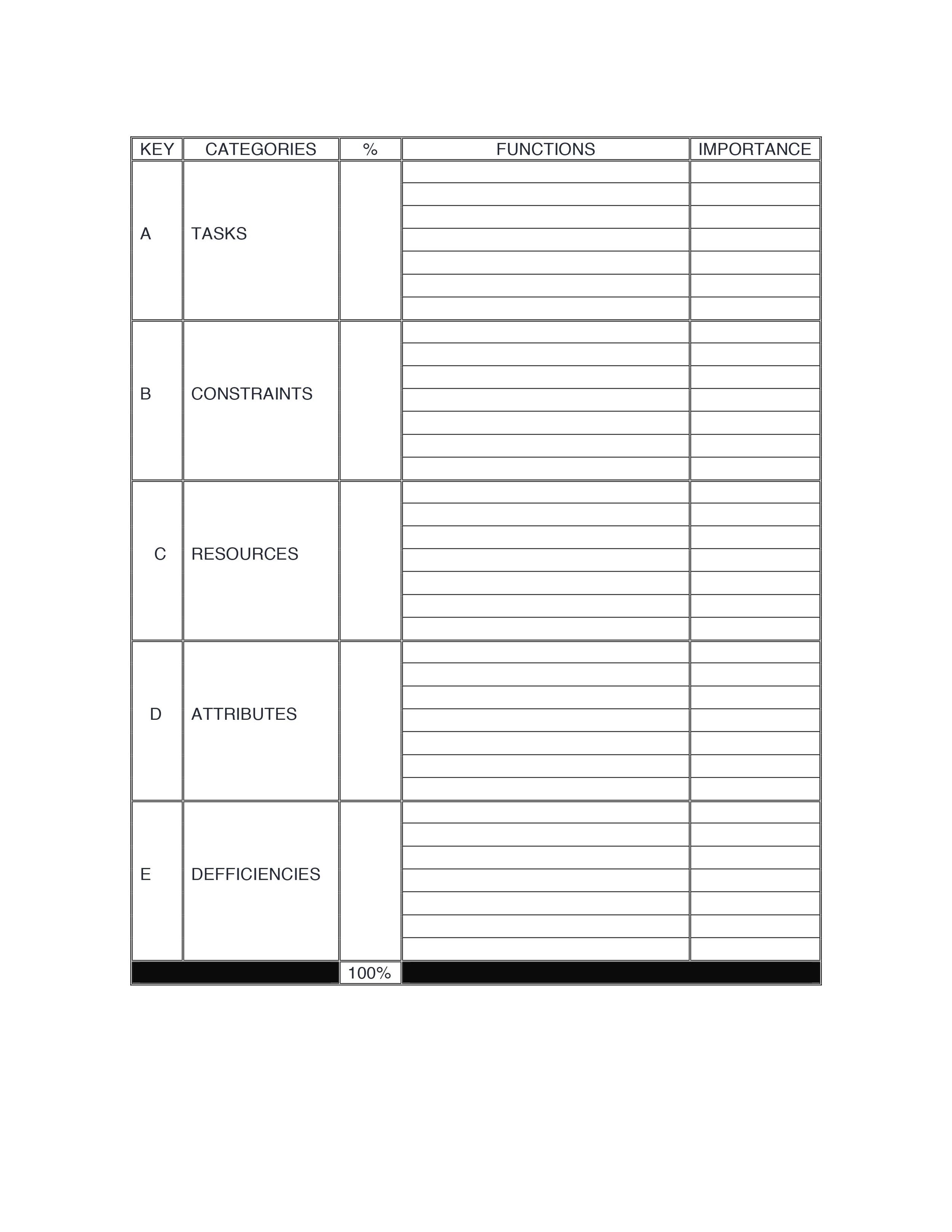

Table of Evaluation Parameters

The 5 parameters noted form broad, vague categories generally applicable to the job. (If you feel more categories are warranted, add them.) A weighting factor will be applied to each. They will be subdivided into specific tasks, identification of particular attributes and deficiencies, and an enumeration of the resources and constraints. Each will be compared to another to determine its “rank.”

To start this evaluation, examine the table. Notice that it has five columns.The first column lists letters A – E. These correspond to the five parameters that are identified in the second column.

The order is not important and the only reason we use labels in the first place is as a kind of shorthand. In the third column, write the percentage of the president’s job that you think each parameter is worth. The total must be 100%. For example, you might think that showing a task is contemplated or in progress is more important than how well the task is actually performed. In such case, you might say that 25% of the president’s effort should be devoted to showing attention to the task, but that the ability to satisfactorily complete it is only worth 10%. In this example, you might also then consider the deficiencies to counter-weigh the attributes also at 10%. If the resources to accomplish the tasks of the office are significant, they may be valued at perhaps 35% leaving the constraints at 20%. The fourth column contains seven rows per category. (Make more if you wish, but seven is probably enough for your evaluation.) You then identify seven tasks,functions or other criteria that you believe are needed to “make” a president. For example, under tasks, you might list “develop foreign policy.” Under constraints, it may be “work with hostile congress” and under attributes, it may be “prior experience,” and so on. Use the fifth column to rank the tasks, function or criteria in order of importance, “1” being most important.

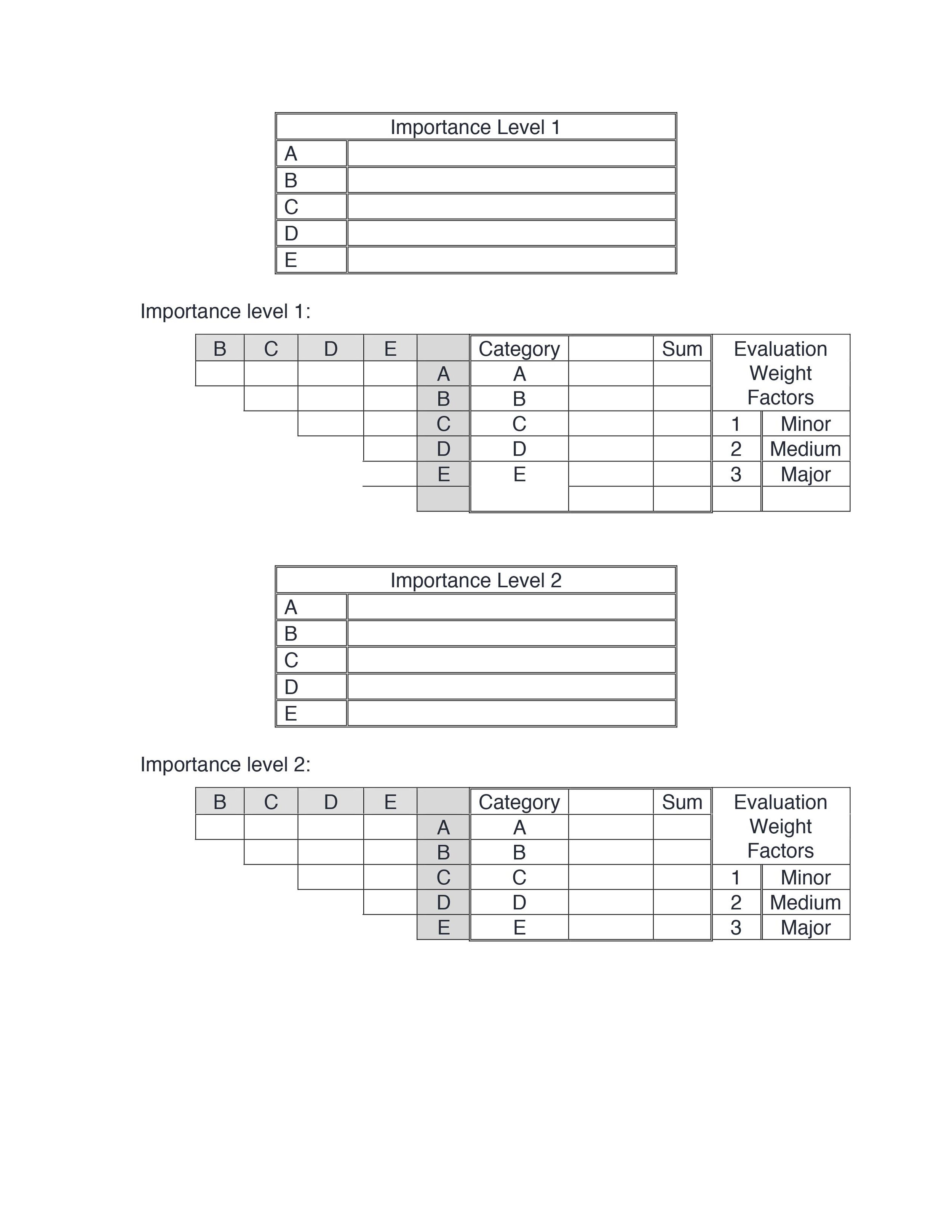

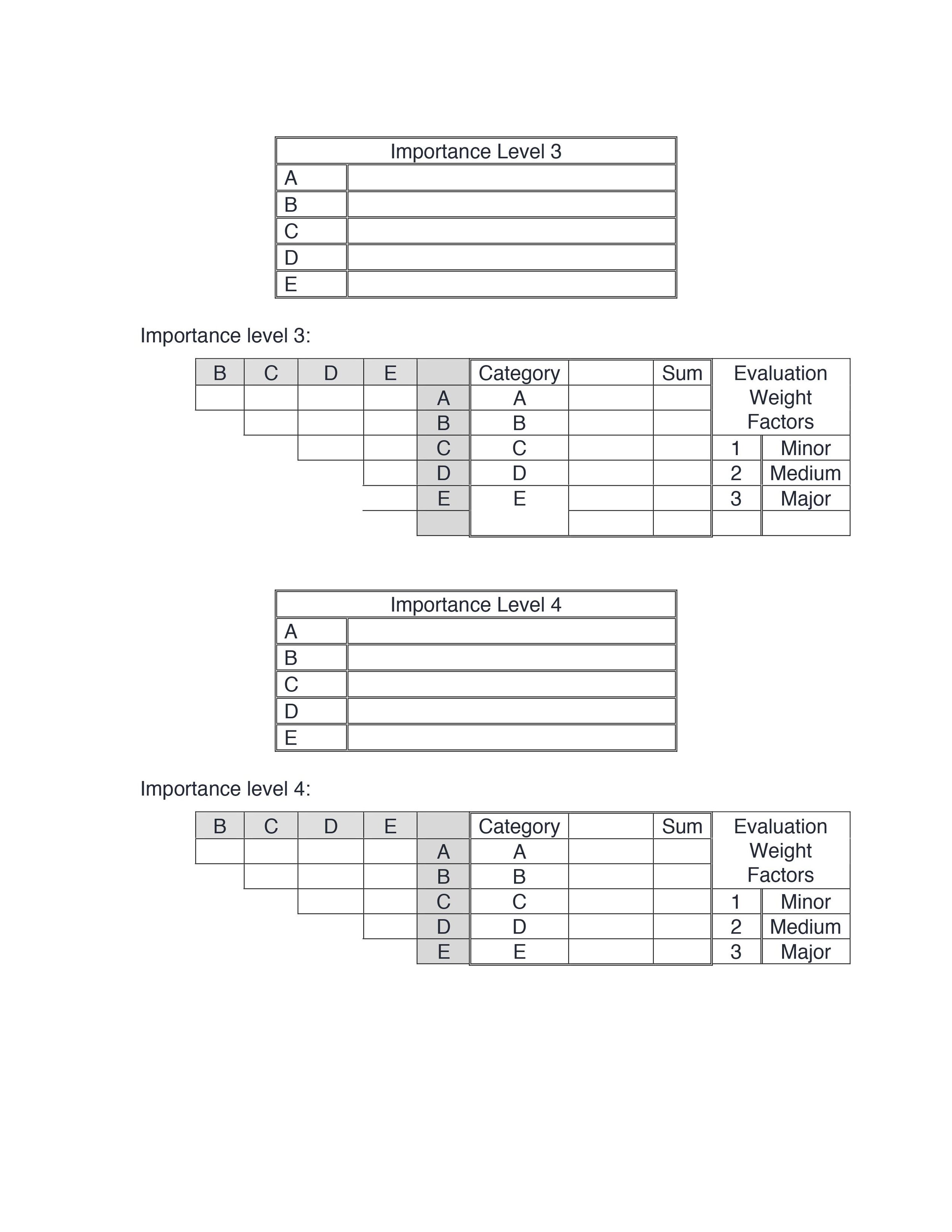

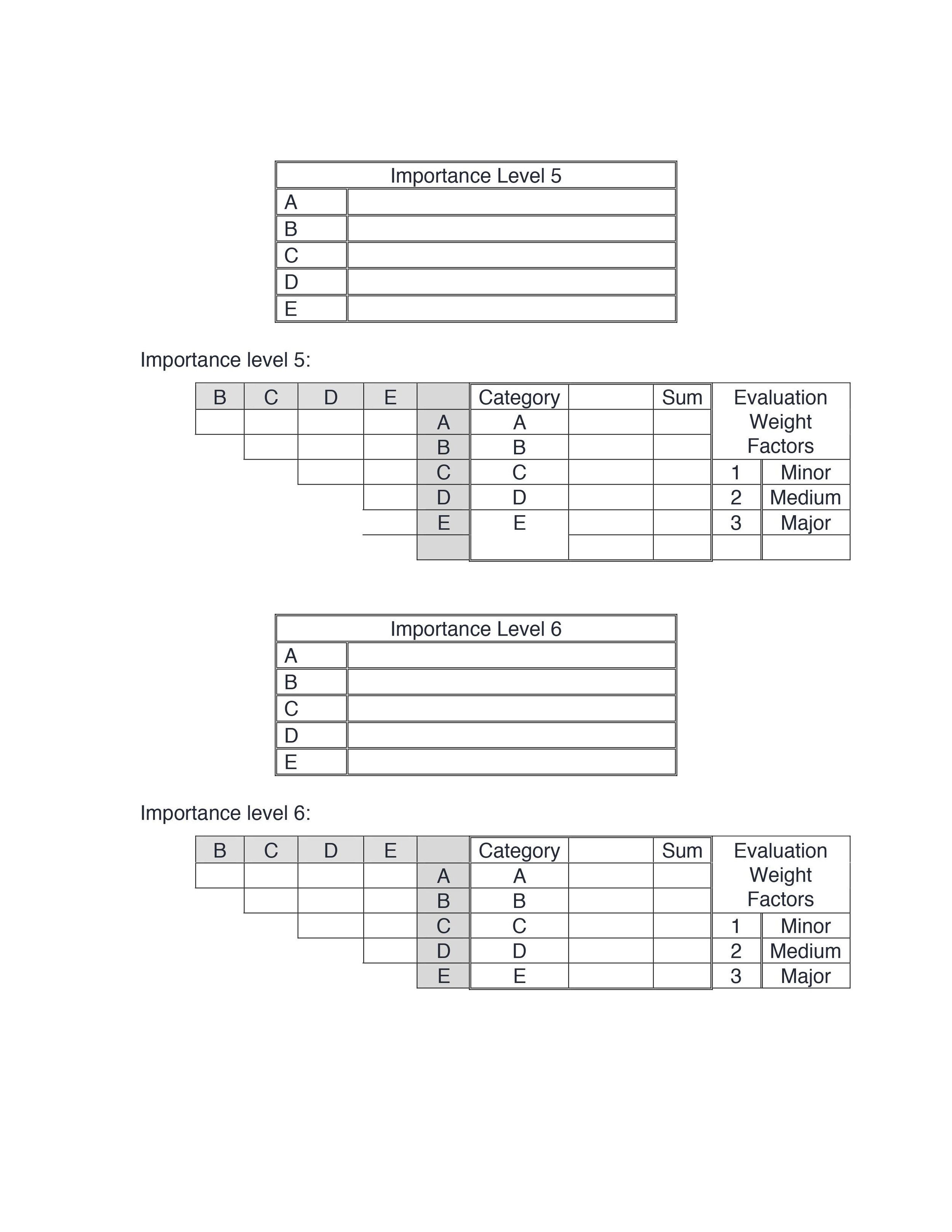

Compare the function identified as most important to you in one category to each of the most important functions in the other categories. Use the Evaluation Weight Factors to show the magnitude of importance. Thus, comparing the most important functionin category A to the most important in category B shows that A has a major difference in importance compared to B, and so forth. Then, sum the results for A, B and the others.

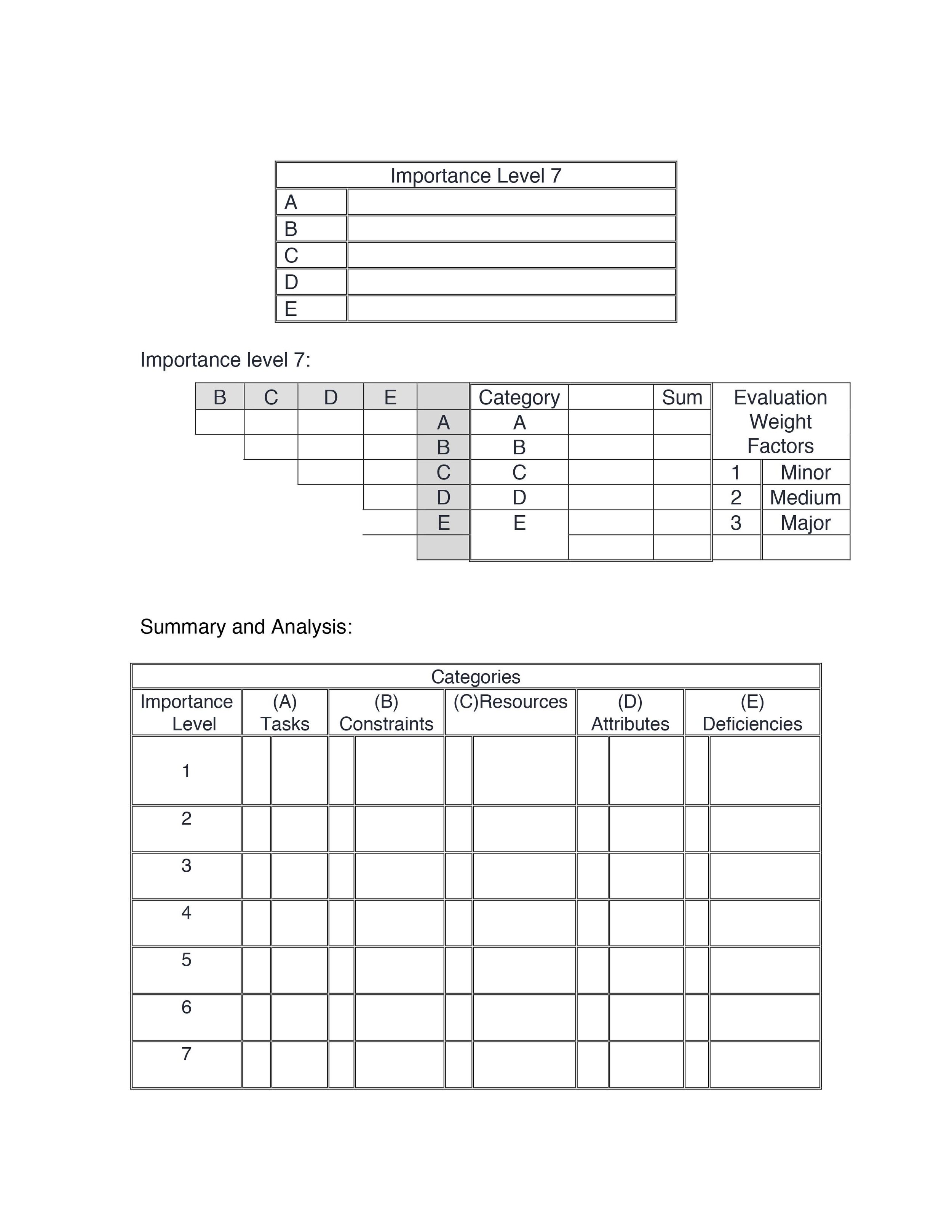

Though simple, this can be confusing.Let’s walk through it:First, list the factors or tasks you labeled “Importance level 1”. In the example, these are:

Second, consider A and B. Which is more important: To unify the people or to know that the money supply is finite? In the example, unification is more important and the distinction is major. We write “A-3” in the box under column B (intersecting with row A). Then compare A and C. Is it more important to unify the people or communicate goals. Here, also, the importance is deemed significant so “A-3” is written in the column under C. The same thing is done to compare A with D, then A to E.

Next, compare B and C. Is it more important to recognize a finite money supply or to communicate goals? And is the importance minor, medium or major? In the example, communication is substantially more important than recognition of a finite money supply so “C-3” is written in the box below C on the B row.

Repeat this procedure to compare B to D, and B to E. Then, sum the individual weight factors for each item. In the example, “E”, “Does the candidate flip-flop on issues?”, is most important. It means that what is desired is a president who does NOT flip-flop on issues; one who is has considered an issue carefully and stated his/her position on it, not changing the position to suit mere changes in the direction of the political wind.

Then apply the worth percentage that you value the categories. In the example this would be 25% for “A,” 20% for “B,” 35% for “C” and 10% for each of “D” and “E.” Here the tasks the president should attempt or accomplish are 7, constraints are 1.8, resources are not important, attributes contribute 1.1 and deficiencies count 1.8.

In this example, it means that the factor of overwhelming importance to the evaluator is actually tackling and accomplishing tasks that are deemed critical to the nation; balance the budget, maintain a strong military and promote the technology necessary to help the United States maintain its competitive edge. The constraints under which the president operates are deemed much less important than just tackling the job! The same thing with resources: The expectation is that the president will get the job done and not make excuses about what it takes to do that job. Similarly, good communication skills are very important and a candidate who cannot get the message across will suffer. The same thing goes for flip-flopping on the issues. Nevertheless, getting the job done is what voters are likely to embrace.

We have examples from recent presidents. Ronald Reagan had strong character and great communication skills. He emphasized military preparedness. George Bush Senior’s pledge not to raise taxes did not last very long and may have cost him the election against Bill Clinton who, by the way, was a gifted orator. In the 2008 election, Barack Obama used his communication skills effectively against John McCain who, many voters decided, did not show great strength of character. (At least one Jewish US Representative stated that he supported Obama because he would be “tougher on Iran.” Clearly, perceptions matter.)

On the basis of this evaluation technique, any candidate who can demonstrate that they possess these characteristics is likely to be elected when positioned against one who is deficient. Thus, you have an objective tool -- a “yard-stick” -- by which to measure a realcandidate. If you apply the procedure to leaders known as “great presidents” you will see how they stack up compared to your ideals. Then scour the field of candidates in whom you MIGHT be interested. Use the same functions you developed to evaluate them as shown in the model. This procedure is likely going to take you a while. It might be best to work with others in a group. In any event, it is exacting and – unlike campaign rhetoric laced with emotion – it permits you to view candidates based upon a fixed criteria that YOU developed. This means that despite bias — and we all have bias — your evaluation will necessarily be consistent and objective.

Appended to this technique are blank forms to help you get started. Feel free to photocopy and use them. If you want to expand the method, feel free to do so. If you get stuck anywhere along the way, send me email, contact me through Facebook, or makecagoldenagain.org. I’ll do my best to help you.

Jay L. Stern

To download forms, click here: